Ships bound for Cuba

in the early 20th century carried with them blankets, fabrics, and rags—typical exports of the Catalan textile industry at the time. Some of these goods were produced at Can Bagaria, an old wool and cotton textile factory built in 1925. Designed by Modest Feu i Estrada, the factory contributed—just as others did across the Barcelona metropolitan area—to the industrial development of the city.

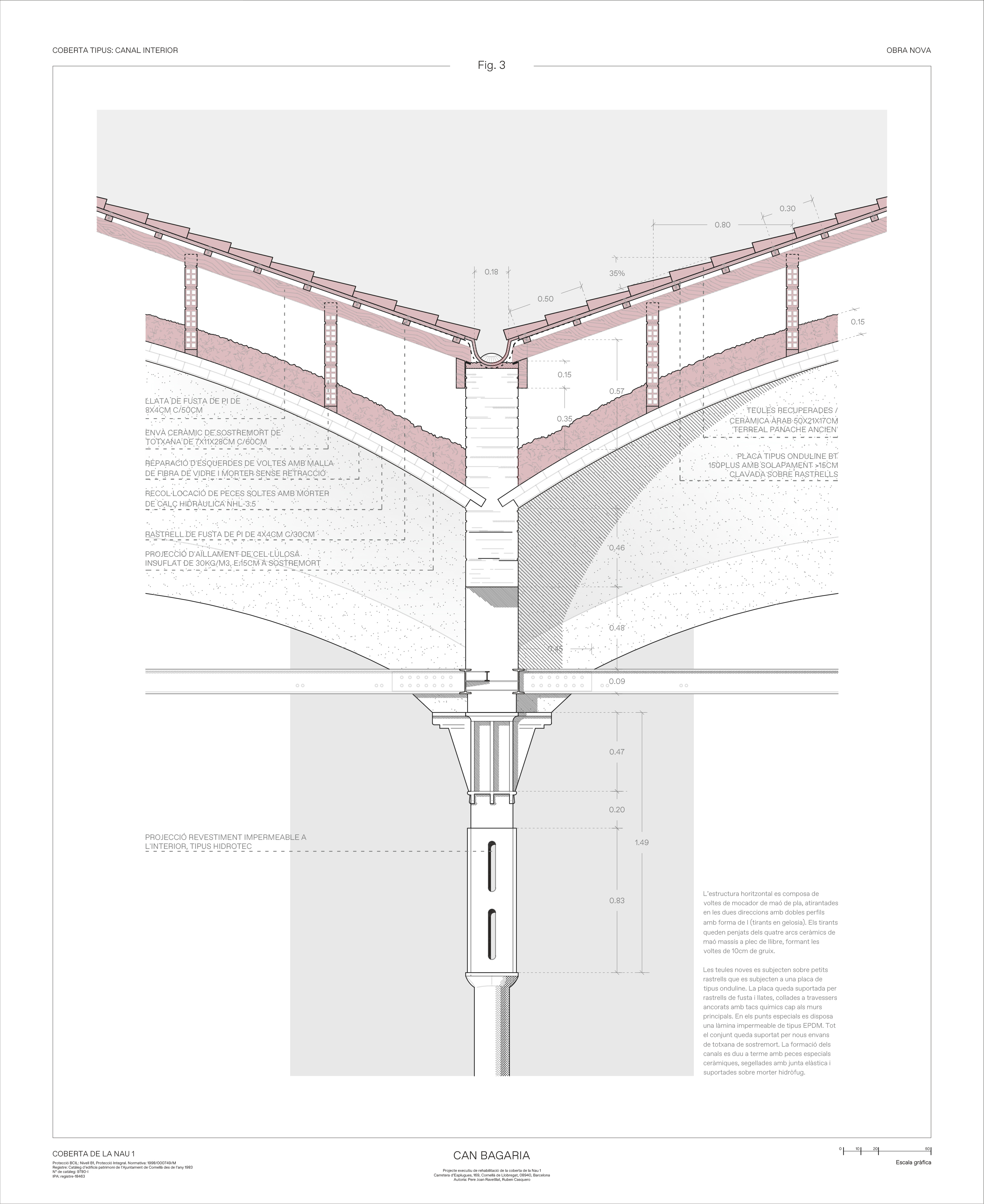

The commission involved restoring the roof of the central warehouse. This

is a structure built with the ingenuity and economy characteristic of

the era: a modernist warehouse, both in its time and in its structural

solutions, yet featuring decorative elements rooted in a certain historicism.

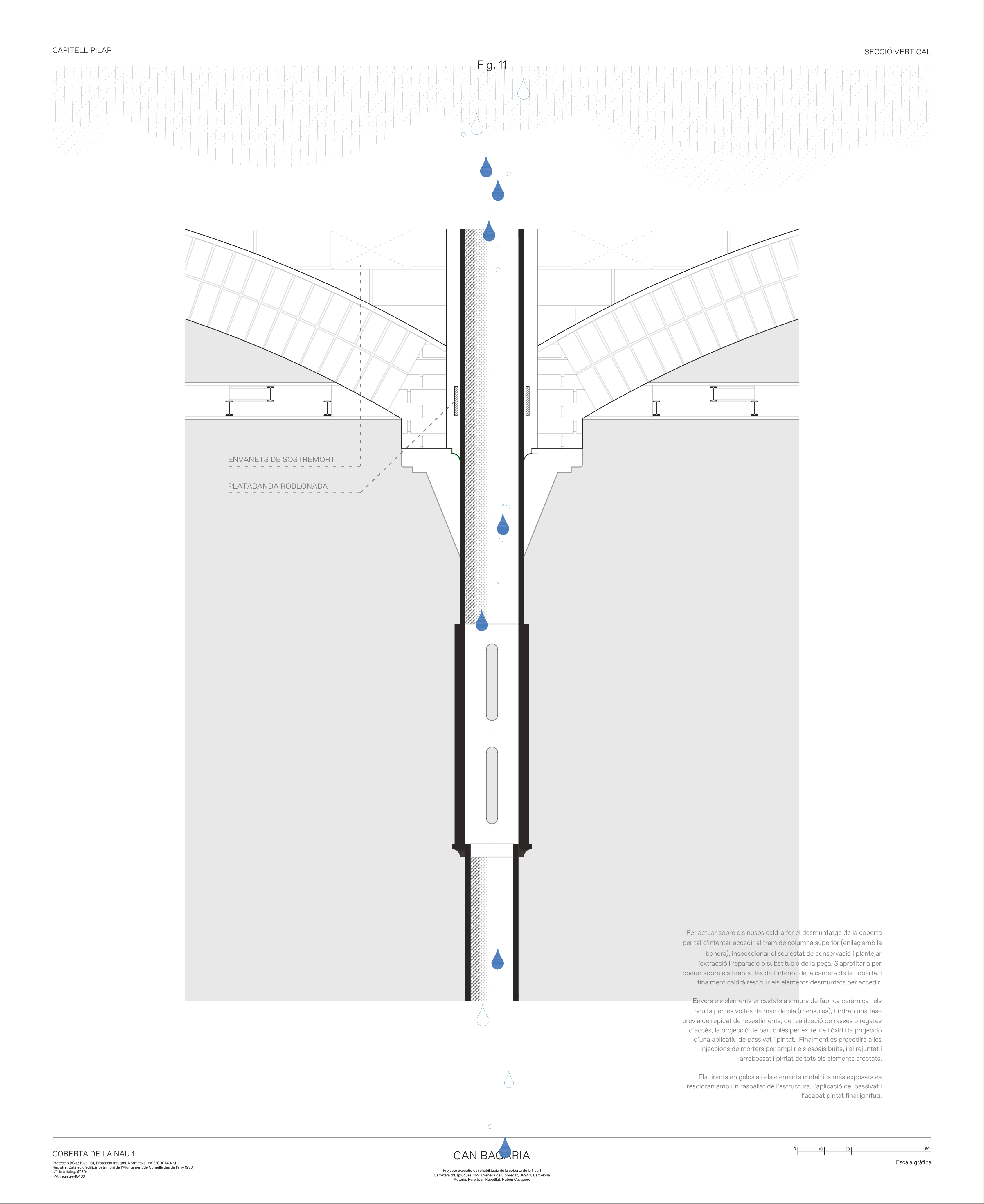

The warehouse consists of a grid of cast-iron columns and tie rods

supporting Catalan vaults. Rainwater drains through the interior of the

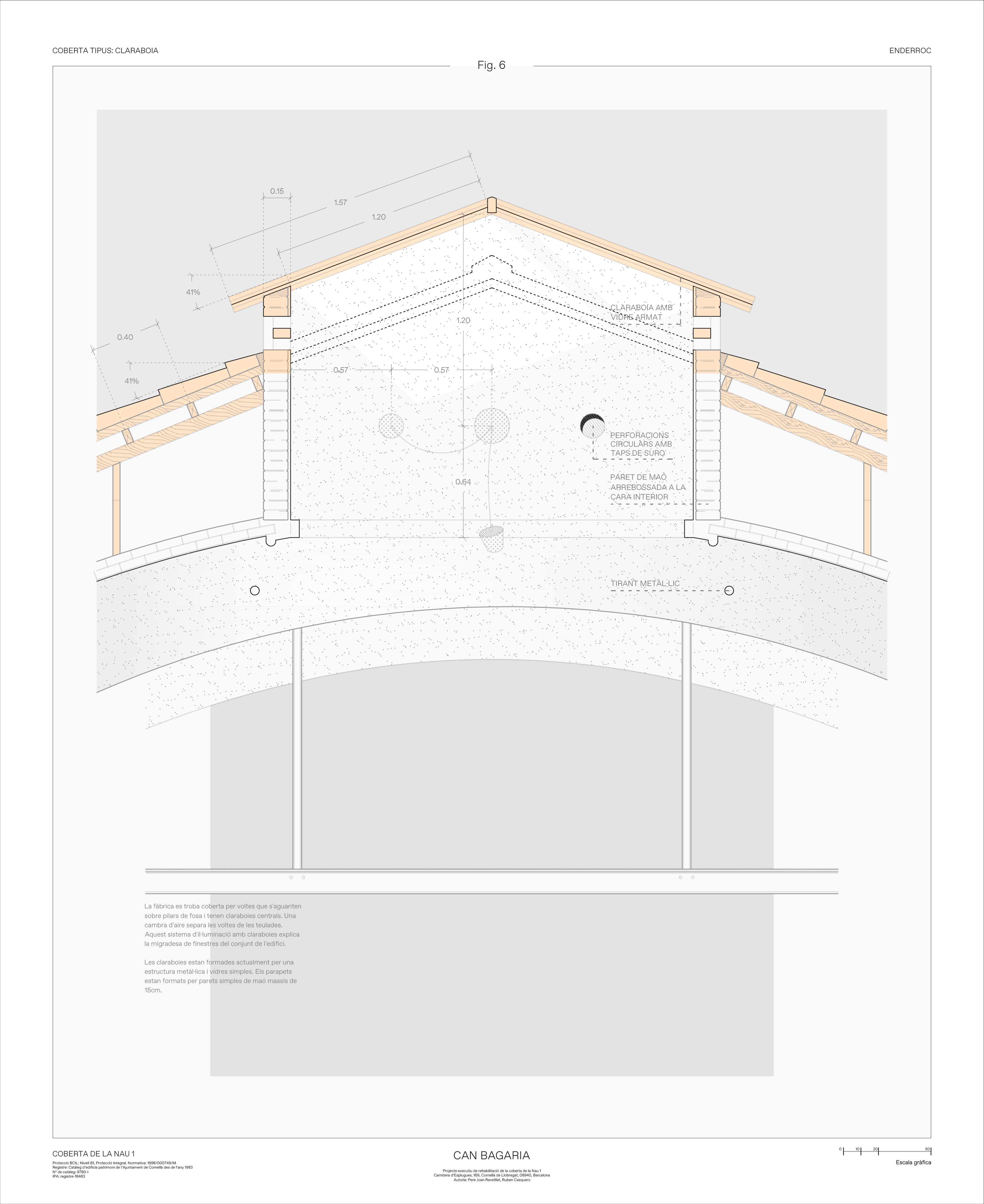

columns, and at the center of each vault rises a skylight. These skylights

diffuse even light throughout the space, allowing for austere, windowless

façades. The roof, therefore, not only fulfills its conventional

roles—waterproofing and protection—but also doubles as a façade and masquerades

as structure. Our fragmented contemporary perspective prevents us from clearly

seeing where a roof like this begins and ends. Restoring this roof is much like

restoring an entire building.

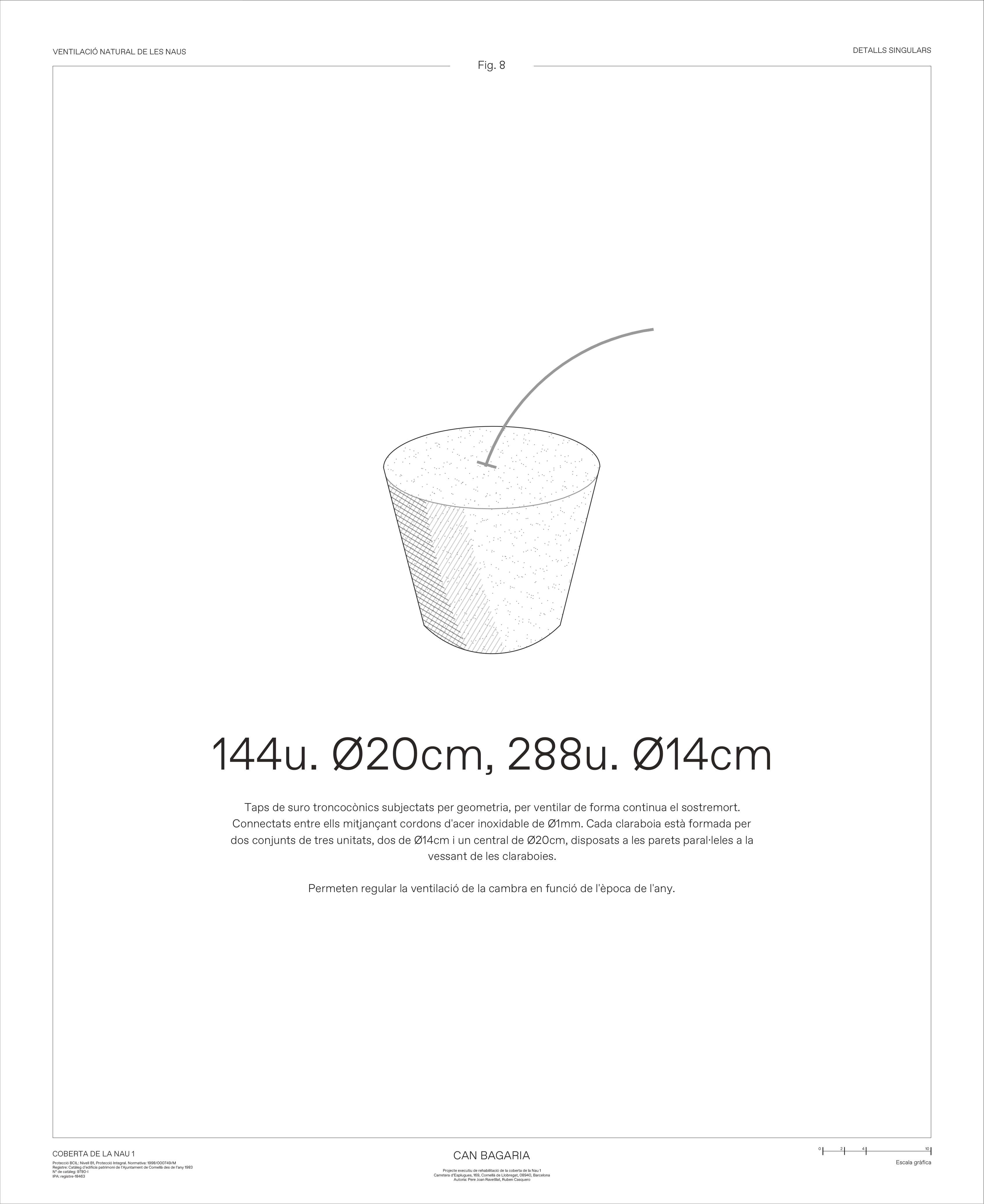

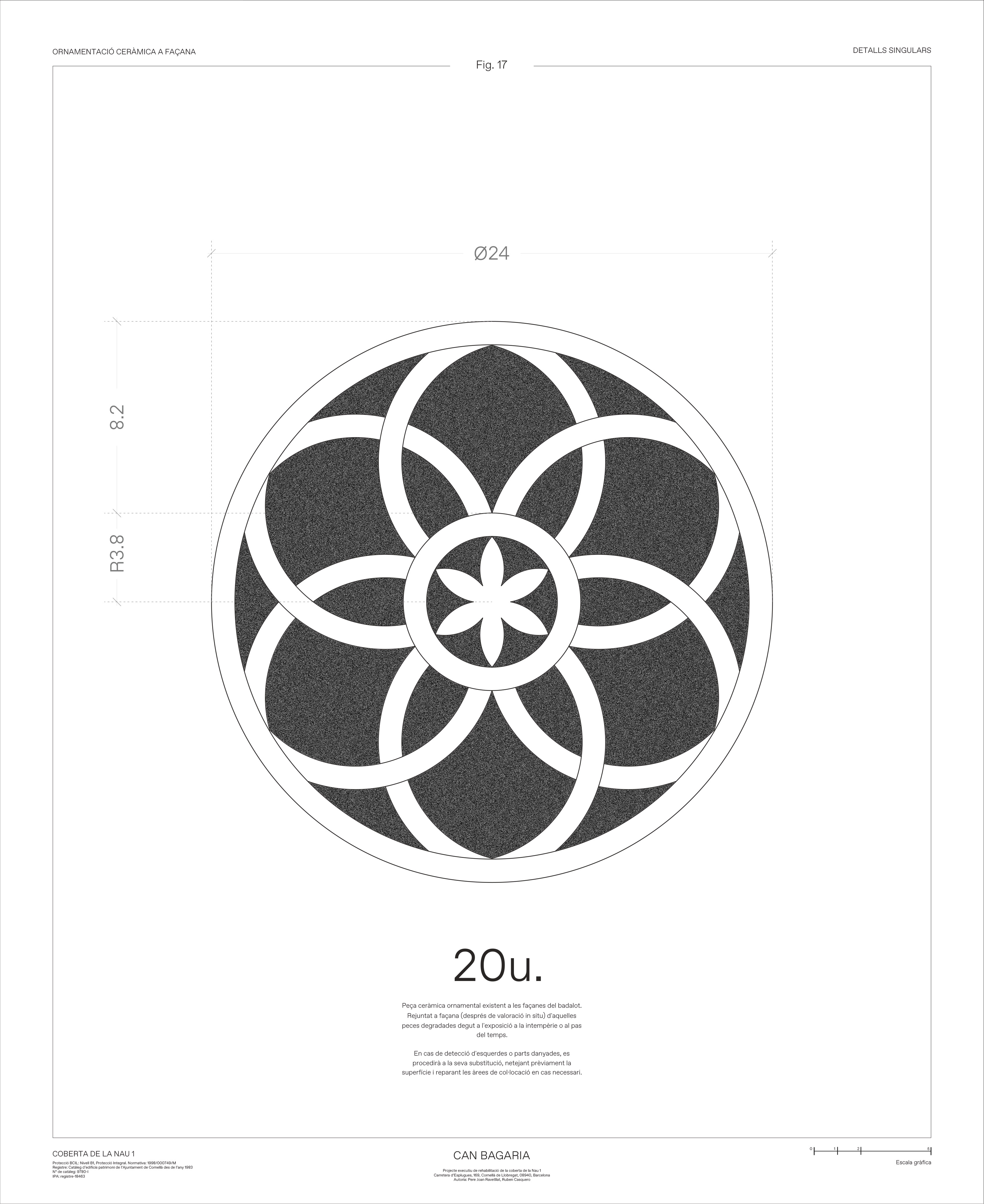

The proposed intervention addressed three objectives. First, to protect the existing structure as a practical duty—without fetishizing the old or engaging in reverential nostalgia. Second, to look toward the future by improving the building’s thermal performance using an organic-based insulation—concealed so as not to compromise the symbolic elements of the building and to avoid the usual conflict between heritage restoration and regulatory requirements. Third, to reveal the architectural strategies uncovered through the study of the building—for instance, the cross-shaped vents that ensure continuous air renewal; the cork plugs that allowed occupants to adapt the interior to seasonal changes; or the ornamental façade elements that protect the drains. These strategies were not part of the building’s remembered narrative because they were considered common sense.

Roofs are sometimes stained black by photovoltaic panels and vanish

beneath mechanical installations. So what color is a roof? Is it that

technological black? The blue of a water roof? Reflective white? The colours of a garden green roof?

One of the hallmarks of the modern movement in architecture was its rejection

of traditional pitched roofs, asserting instead the flat roof as the norm. The

debate then was formal. Today, the contemporary roof is, in contrast, a matter

of color.

Listed as a BCIL (Cultural Asset of Local Interest), this warehouse is

part of the city's industrial heritage. But when something is listed, what

exactly is being protected? Typically, it’s the stones—the elements, the

material. Since the 1990s, however, there has been growing interest in

intangible heritage. This type of knowledge doesn't appear in heritage registers,

but architecture hints at traces of behavior and specific knowledge rooted in

place. Singularities that speak to how a people inhabit a territory and a

climate—traces that can speak just as eloquently as the stones themselves.

©2026

Legal&Cookies

Legal&Cookies